The spiderweb entrepreneur

I’ve developed some ideas based on running a bootstrapped startup for about five years now, and I want to write blog posts about some of them. We write a very sales-focused blog on the CrankWheel site, so instead of posting there, I’ll be posting them here on my personal website.

This is my first post on this subject. You can subscribe to updates if you’d like to read my future stuff.

The first idea I’d like to discuss is what I see as a very efficient (capital and otherwise) approach to building a business, starting as a solo founder. As I have a co-founder in CrankWheel, I haven’t actually gone this exact route, but I’ve done most of it as there was a period a couple of years back in CrankWheel’s history when we shrank it down to just me as the only full-time contributor, where I was essentially at the “Ray” stage that is discussed below and then progressed through the other stages as the business grew again.

Quite a lot of pundits will tell you that when you start a business, you should work “on” the business and not “in” the business, i.e. you should run your business immediately in a way where you are not needed for the day-to-day operations. As you’ll see from the below, I don’t subscribe to that philosophy. For a bootstrapped business, I think you need to do both: You need to be the key employee of the business at the start, and then over time scramble your way as quickly as you can up to spending more and more and finally most of your time working “on” the business rather than “in” it. I also think the progression I describe below is a fairly structured approach to achieving that.

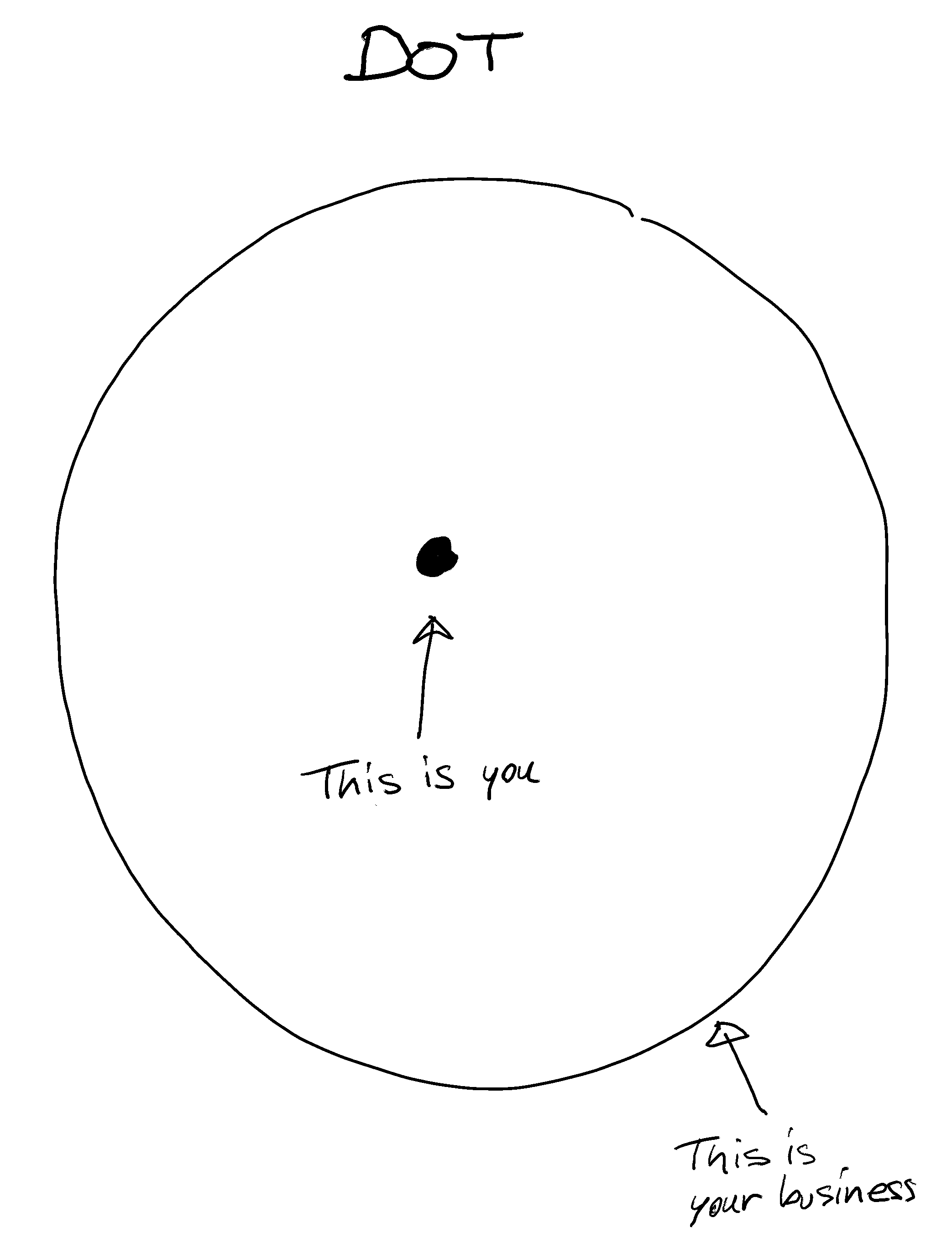

Starting point: Dot

When you’re just starting out with a business idea, I think one of the most efficient ways to do it is as a solo founder. It can be great to have a co-founder, but for clarity in this post I’ll assume you’re starting solo.

A solo founder is like a Dot at the heart of the business, working all alone.

The challenges of starting solo are that you have nobody to lean on, which can be especially hard from a motivational perspective and sometimes from a mental health perspective. Nobody but you understands the ups and downs and the emotional challenges of building the business, so the people you might lean on for support such as your spouse or friends, while they might listen, probably don’t fully understand. Other founders get it though, even if they’re not running the same type of business, so try to make friends with some of them.

Being alone also means there’s nobody else to do anything: Everything that happens in the business, happens because you do it.

This has a very strong focusing effect, driving you to work on the most important stuff in the early days, and skip the rest. What’s it going to be, spend this week talking to potential customers and building the MVP, or establishing a social presence? Easy: You can’t do both, so you do what’s most important to move the business forward, building a no-frills MVP based on customer feedback.

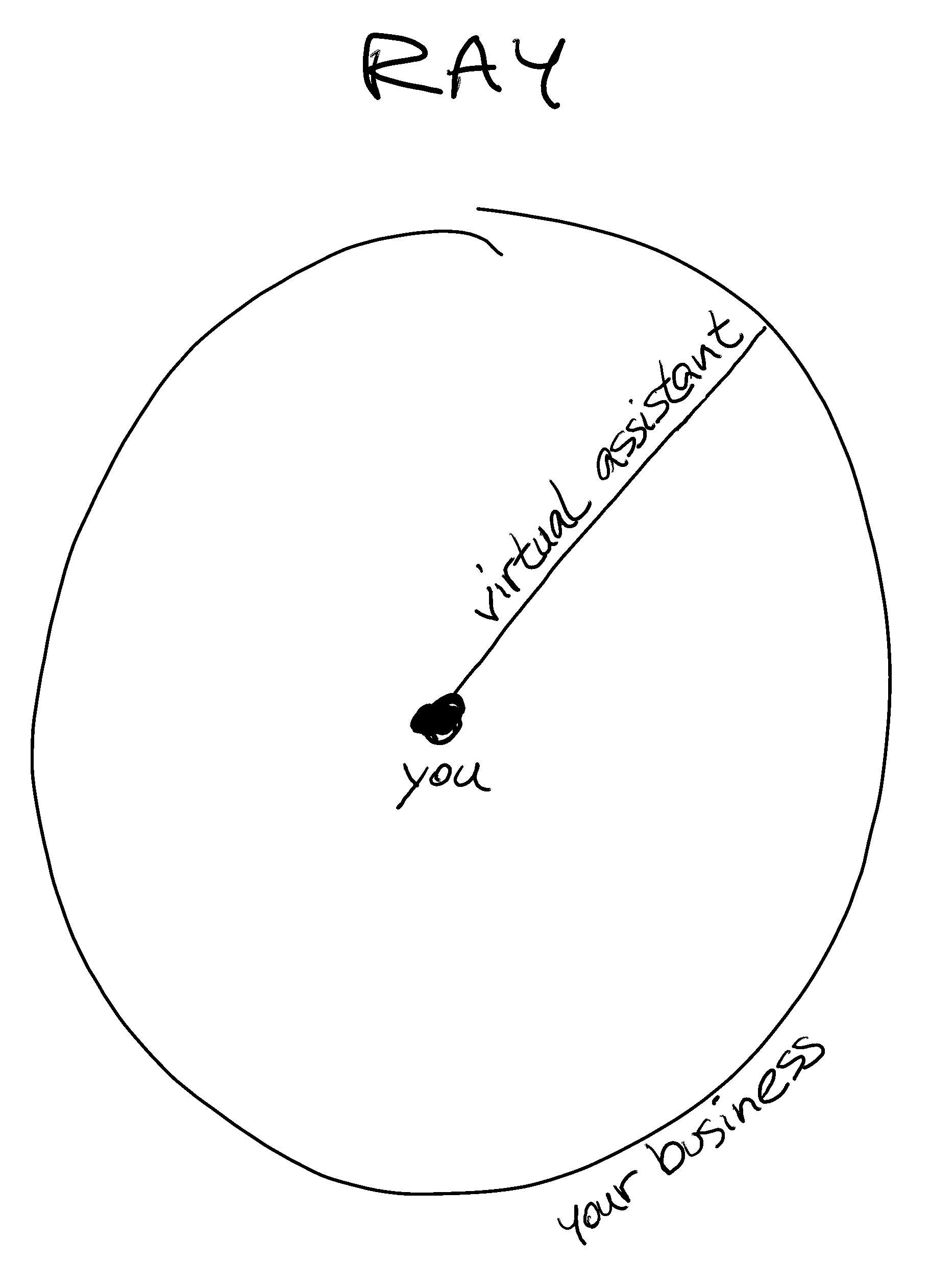

Upgrade #1: Ray

As soon as you can afford it, it’s worth upgrading to a /Ray/: You’re still at the center of your business, but you’ve got yourself a virtual assistant (VA) helping you with various rote tasks, which leaves you more time to focus on more impactful tasks.

Having a virtual assistant is especially useful as soon as you start various repetitive sales and/or marketing activities or as soon as you need to provide customer support. Over time, you can train your VA to take over a lot of tasks that you initially perform yourself.

Delegating to your VA

Delegating tasks to your VA is something you should think of as a continuous task you chip away at every week, not something you can do all at once. As an example, you might have a progression like this for a task to work through inbound freemium leads for your business:

- Do it all yourself: Trigger a job to gather all inbound leads for a given period, then manually (yourself) go through each of the leads and decide how to handle.

- Do it yourself plus automation: Still working the leads yourself, automate or semi-automate some parts of how they are handled, e.g. make it a one-click thing to handle a particular type of lead in a particular way, sending them a certain type of welcome email for example.

- You initiate, your VA executes: Still triggering lead processing yourself, teach your VA how you would like leads to be pre-processed before you take a look at the 10-20% where your VA is unsure.

- Have your VA initiate: Next, delegate the triggering to your VA, turning the initiation of the task on its head - instead of you reminding your VA a few times a week to pre-process leads for you, you get a reminder from your VA a few times a week to look at the several leads they were unsure about.

- Sharpen the saw: Over time, train your VA further on how to handle more specific types of leads manually, in addition to the semi-automated approaches you had before, further lowering the portion of inbound leads you might need to look at yourself.

This kind of gradual offloading over time of your rote tasks to your VA is something you should continue doing over time. In fact for any task that you’re considering when planning your week, consider whether you can:

- Teach your VA to do it, either right away or over time, using an approach such as outlined above.

- Automate it. There’s a balance here; if an automation is easy, it’s likely worthwhile. If it’s hard, you may be better off teaching it to your VA rather than fully automating it, or automating part and having your VA do the rest.

- Delay it. Sometimes a task is not urgent, and quite often, the need (or perceived need) to perform it goes away if you just wait a bit.

- Completely skip it. This is the ultimate productivity enhancement if it’s an acceptable outcome for your business that the task does not get done. The power of saying “no” is a key factor here - a subject for another blog post.

One caveat is that before you delegate a task to your VA, it’s best if you’ve already done it yourself often enough to have a good idea of how to do it efficiently and with high quality.

How to hire a VA

To hire a VA, there are many agencies you could go with, or you could use an online freelancer marketplace like Upwork to hire directly, this is what I did. A VA is a tricky hire where you need to build quite a lot of trust over time, and work together pretty closely, so you need to hire carefully and be willing to fire fast if it turns out the person you hire isn’t a great fit for you. My recommendations for maximizing the chance they are a good fit before hiring them are:

- After posting your job and receiving hopefully dozens of candidates, shortlist 6-12 of them based on their cover letter, answers to questions you asked for answers to from candidates, past experience, ratings on Upwork (or other job board you’re using) and so on. I should also mention that in my experience, a job success score on Upwork of 95%+ is a very strong indicator of reliability, whereas the 1-5 star rating is much less indicative. The job success score is not always shown, and freelancers without one can be great.

- Interview the short-list “in person” i.e. via a Skype or Zoom or similar video call. This call is where you get to see their language skills in action, which to me is one of the most important aspects of having a good relationship with a VA, you need to both fluently speak a common language (e.g. English) well enough that there are no misunderstandings, and if your VA is communicating on your behalf and/or on behalf of the company, it’s very important that they are proficient enough in the company’s operating language to do so. This is also where you get a feel for personality fit and culture fit. Finally, the interview lets you set expectations for what the rest of the hiring process will look like.

- For the 3-5 candidates you think are the best based on interviews, offer each of them a starter project, fixed scope and fixed pay, ideally all starter projects identical so you have a direct comparison. You should get very specific with the project goals, this lets you see if they are precise and read your instructions properly. You should also make sure you cover as many of the relevant skills as possible; for example if you’re hiring a programmer, it’s great if they know the programming language and environment that you’re working in, but whether they also know how to work with GitHub and how well they respond to receiving criticism in code reviews also matters a lot. Although my primary recommendation is to get pretty specific in your project goals, I also suggest leaving some parts of the project open to interpretation. The best candidates may delight you by overdelivering on the vague parts.

- If you are happy with one of the candidates after the starter project, hire them in an ongoing by-the-hour project - if not, maybe give some more of your shortlist the starter project, or advertise again or in another marketplace. Don’t settle. Be ready to fire fast if things don’t look right within the first couple of weeks. The most effective relationship with a VA is one where you build trust to a level where they get to have access to a lot of your systems and data, very likely including your email, and therefore it is imperative that you feel comfortable with your VA and that they exhibit trustworthiness and strong principles from day one.

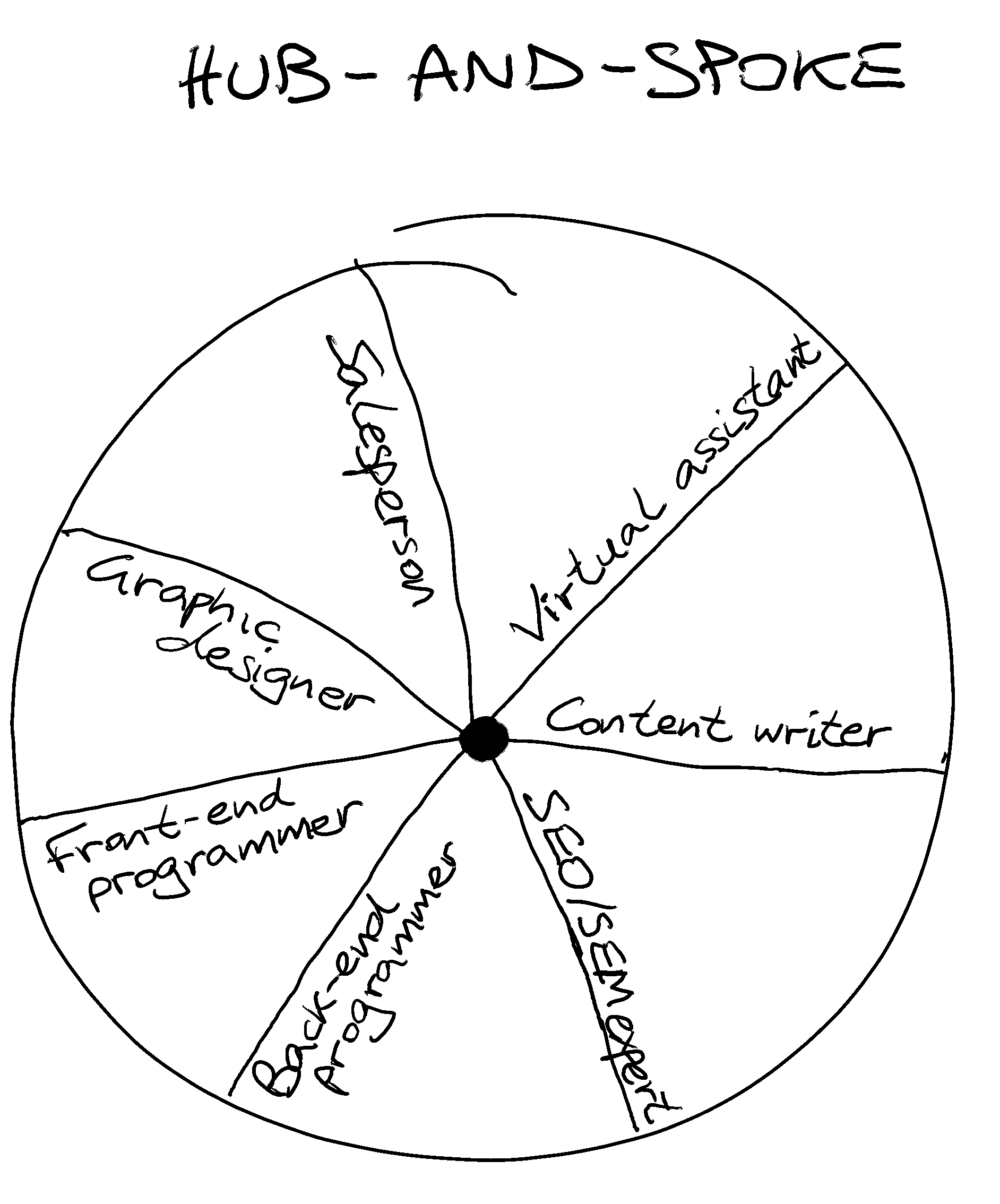

Upgrade #2: Hub-and-Spoke

The next step after the “Ray” model is the Hub-and-Spoke model. You’re still at the center of everything and everything flows through you, but you’ve got a number of specialists working for you in addition to your generalist VA. Some of these may be part-time, others full-time or close to it. Some or many of these folks may be remote, that is the route I’ve taken and I recommend it for the huge access to talent it grants you, at (depending on your location in the world) potentially much lower cost than hiring locally.

You can hire online for almost all of your initial “spoke” roles using the same approach I outlined above for your VA, or potentially through relevant agencies. Others you may prefer to hire as employees, whether they are local or remote; how to do that effectively is a topic for another post. When hiring an employee early on in a bootstrapped company, keep in mind that at least in many European jurisdictions, hiring an employee is a much bigger commitment than hiring a freelancer, as you’ll typically need to give plenty of notice and severance pay, which can be a fairly big risk when your company’s cashflow is still tiny and perhaps not very predictable.

Next-level delegating: SOPs

Once you get to the Hub-and-Spoke model, you need to become even better at delegating, and because you may need to scale up one part of your business (e.g., adding more salespeople, or adding another front-end programmer), you may need to train different people multiple times for the same or similar job.

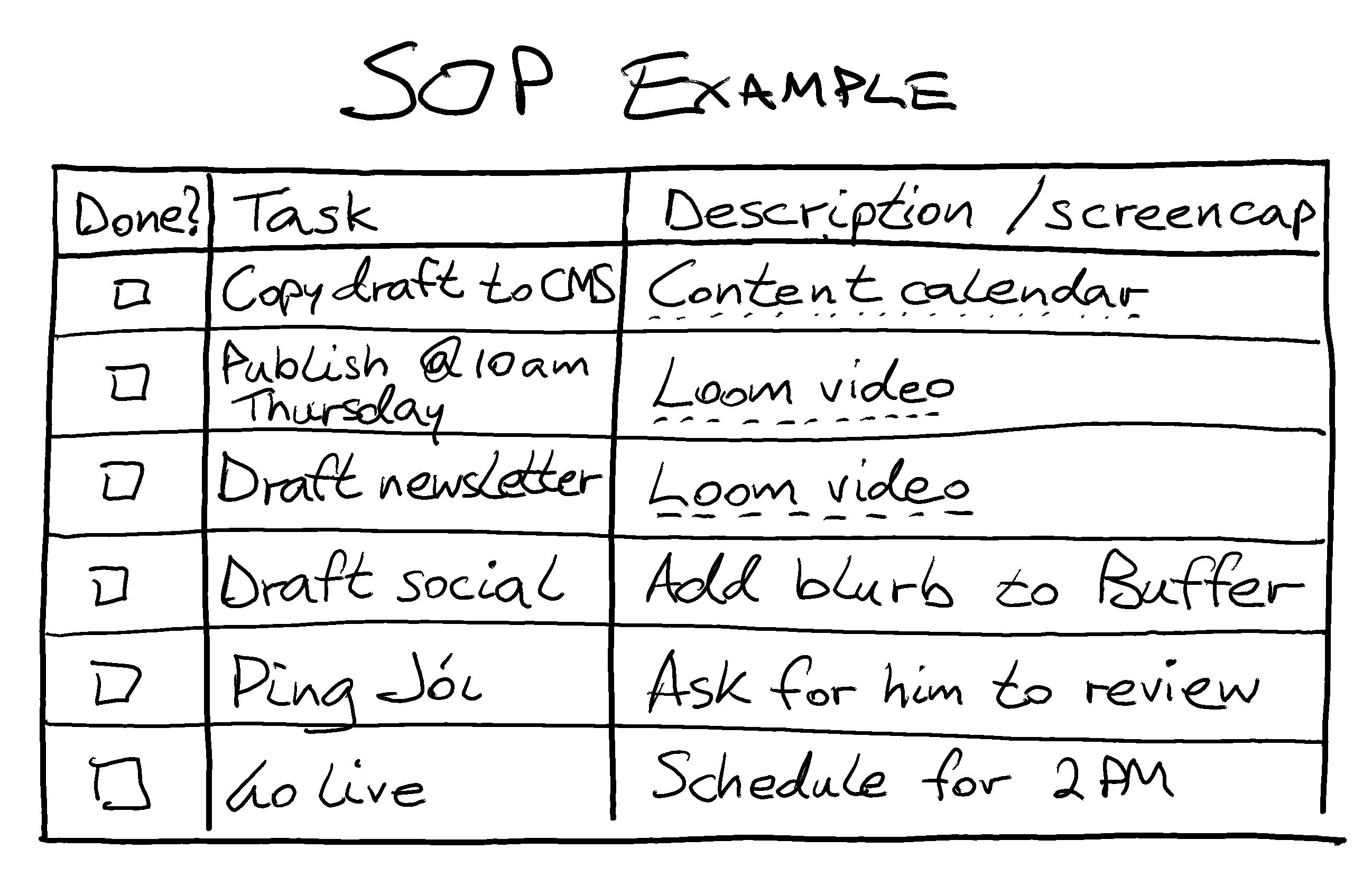

A key approach I recommend to delegate more efficiently at this stage, and in a more repeatable manner, is the use of procedure checklists or “standard operating procedures” (SOPs) coupled with screen capture videos that show how to perform a task.

When I started out using SOPs, I used some online process management tools, but in the end I found that a simple Google Spreadsheet for each SOP is simple, cheap and flexible. If it’s a process where you’re never running two copies of the process at once, all you need is a simple spreadsheet similar to the below. You can make everything but the checkbox column protected so that it doesn’t get accidentally modified.

Simplified example of the SOP my VA follows after I’ve finished writing and/or reviewing a blog post on our content calendar.

If you need the ability to run multiple copies of an SOP potentially in parallel or overlapping, just put the master process in one sheet of the spreadsheet, make that protected, and tell your staff to make a copy of it named for their email alias and date they started running it, when they need to run that SOP.

Recording a screencast video of yourself performing each of the tasks from the SOP and explaining verbally while you do it is one of the best ways I’ve found to document tasks on the SOP. It’s quick, it’s context-rich, and you can probably speak faster than you type, although for very simple tasks just writing the task description might be quicker. The tool I recommend for screencast videos like this is Loom, a free extension for Chrome also available as a stand-alone program.

What you end up with is a checklist that a brand new freelancer or employee could follow, as the detailed training material for each task on the checklist is linked to right there from the SOP document.

Some roles you may need are not routine enough for SOPs to cover everything. A good example is product development. For these you may have SOPs for some important things such as your QA process, your release process, and best practices, but a lot of the work will by its nature be new work. For this type of work it’s important to develop ways to communicate intent and design in ways that are well-understood by everybody involved, for example a reasonably-standardized format for specification documents and a reasonably-standardized approach for communicating things such as user experience, technical architecture and more. Your main focus in order to prevent yourself from becoming a bottleneck again should be to work at the level of specifications and mockups, strategic plans and project plans as much as possible. I won’t dive deeper into that for now.

Example specialist roles

There are a lot of specialist roles you can consider hiring for in the Hub and Spoke model. In some cases, one person can fill multiple roles, in other cases it’s best to hire the most focused specialist you can. Some ideas to consider are:

- Graphic artist

- Website developer

- Front-end developer

- Back-end developer

- User experience designer (UX)

- SEO/SEM expert

- Content writer

- Copywriter

- Market researcher (possibly a short-term position)

- Account Executive (big guns salesperson)

- Sales development rep (prospecting and initial contact/qualification)

- Social media lead generation specialist

- Customer support rep

- Customer success rep

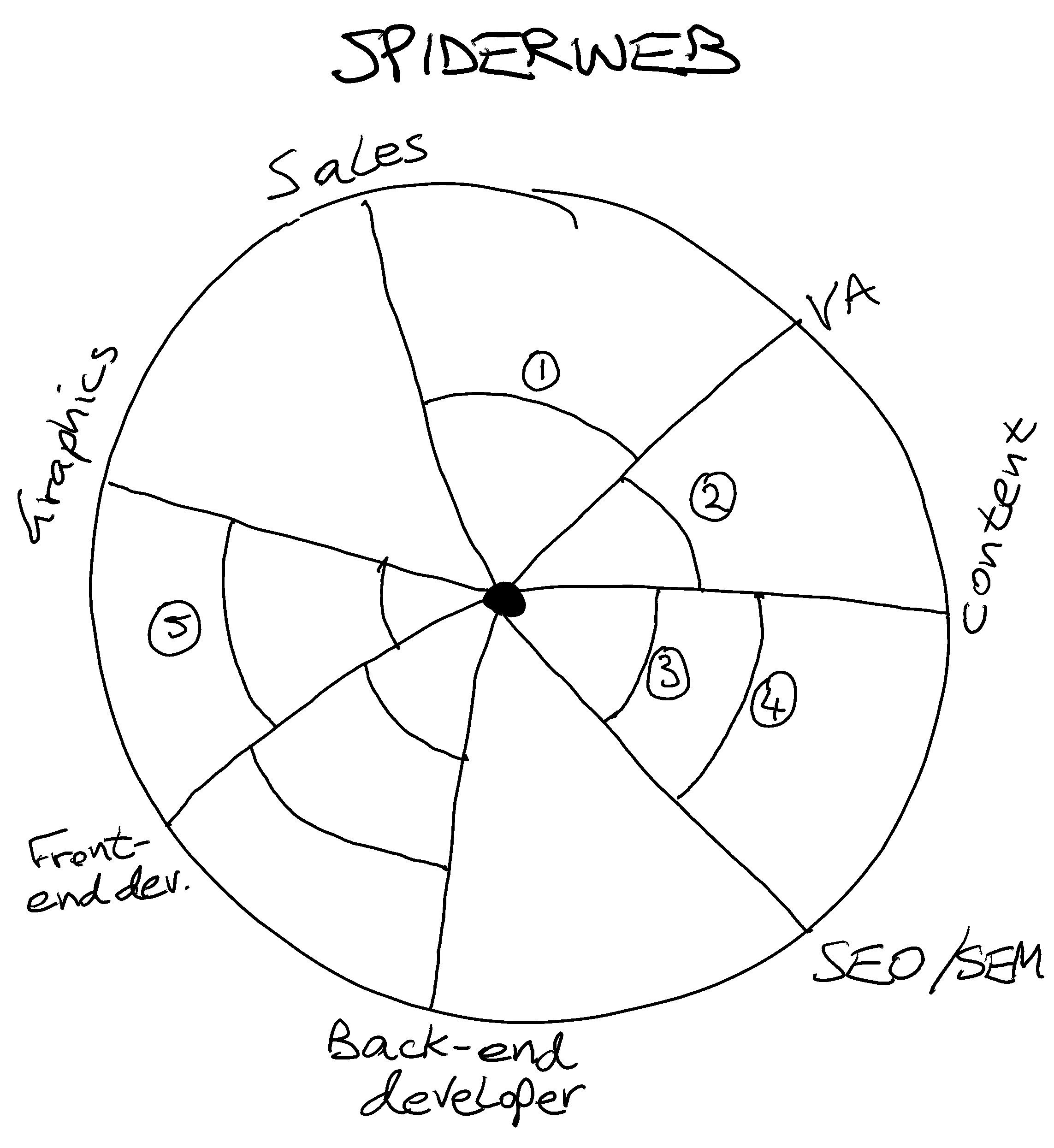

Upgrade #3: Spiderweb

While the Hub and Spoke model is quite efficient, you can become a bottleneck rather quickly since everything is passing through you. Therefore, as quickly as you can after getting comfortable in that model, you should upgrade to the Spiderweb, which reduces that bottleneck pretty quickly.

The Spiderweb is basically about building direct communication between the folks who are the “spokes” in your Hub and Spoke model. As you build several of these bridges the diagram of your business will start to resemble a spiderweb. There are a few simple steps to it:

- Identify a potential direct collaboration between members of your staff.

- Make sure that the SOPs you want them to collaborate on are initiated not by you, but by one of them, possibly on a set schedule or possibly as a reaction to some outside trigger. If you leave yourself initiating each particular instance of collaboration, you haven’t really taken yourself out of the loop.

- Up until now, those two members of your staff might not ever have spoken. Make sure you introduce them properly - jump on a video call with both of them or all go out for lunch if you’re in the same location. Tell them a bit about each other to give them a starting point in their social conversations, just like you would when introducing two of your friends who don’t know each other at a dinner party. Being comfortable (or at least non-awkward) with your collaborators socially makes it a lot easier to do good work professionally.

- Give them insight into each others’ SOPs or areas of responsibility that you want them to collaborate on, and how you expect the typical flow of work to happen. You can create a shared SOP that covers their interactions at this point, if the interaction is complicated enough.

- Make it clear who has authority to request work from whom, and to what degree - if their collaboration is a SOP they shouldn’t need to ask you to approve every case of it, only the exceptional cases.

- Let them know what to do if things don’t go according to plan (until the business matures further, this will usually mean checking back in with you).

- Trust but verify. You’ve now gotten yourself out of the loop in terms of being the bottleneck, but especially early on you will want to verify that the work is happening, and happening in the right way. As a first step you may request being CCed and informed. Later on you could set up automated check-in emails or weekly status reports rather than being CCed on everything. Up to you. Don’t micromanage, but don’t give up ownership either. Until your business is bigger and you have executives reporting to you, or a valuable enough business to give your staff proper skin in the game through stock or profit sharing, you are the only owner and while your staff will want to do a good job, they are unlikely to care the same way you do.

Once you build several bridges between your staff, your Hub and Spoke will start to look more like a spiderweb.

Example collaborations

Some examples of direct collaborations you could build in this model, continuing with the “spoke” roles we used as examples in the previous model:

- Your VA might have a weekly task to perform some standardized prospecting to generate a set of 50 outbound leads each week, that they feed to your salesperson to validate before those leads are put into an outreach sequence. Your salesperson takes over from there.

- Your content writer might write some or most of your blog posts, and deliver them as drafts in Google Docs, with your VA taking those drafts and bringing them over to your blog CMS system for publication, adding an illustration created by your graphic artist, all of this orchestrated from your content calendar.

- Your SEO/SEM specialist could have a monthly task to send a list of the top-performing keywords and keywords they’ve researched as good ones to test, to your content writer, who would incorporate them into upcoming blog posts.

- Your SEO/SEM specialist might be tasked with adding several new “alternative to” paid ad campaigns, and could send a brief of each campaign and the product your thing is being suggested as an alternative to, to the content writer who would churn out the copy for a landing page for the campaign.

- Your front-end developer might be tasked with driving the creation of new user interfaces when needed. To do this he could create rough sketch-like mocks that he would then send after review to your graphic artist for a PSD of how they should be rendered pixel-perfect in the final product to match the overall intended look and feel.

The Spiderweb model is also where you can start to consider hiring project managers over certain aspects of the business; not people managers necessarily, but project managers who orchestrate more complex collaboration between multiple team members. Good examples of this in a software business could be hiring a senior developer with some team leading experience, and having them act as project manager for the product team in addition to development duties, or hiring a multi-talented strategic thinker as a marketer, and having them coordinate collaboration between all the specialists involved in marketing.

In summary

Assuming you manage to grow your revenues reasonably well, you can progress quickly from Dot all the way through to Spiderweb, and you can run an incredibly well-oiled business machine using this model. It can scale a fair bit, and it can be a lot of fun.

However, I wouldn’t recommend staying in this model for much longer than you are forced to. You’ll risk burnout, and you also need to scale up to make yourself less indispensable to the business.

When you have enough profit, or if you decide to take in significant funding, it’s time to think about promoting some of your project managers to executives or hiring outside executives into key roles, as this will allow the business to scale much further.

Once you have your first executives, teach them the progression to the Spiderweb model - it can be similarly efficient for VPs starting with a small department as it is for owners bootstrapping a new company.